Ṣaḍ Darśana: The Six Philosophical Visions India Built

There is a peculiar irony at the heart of modern India's intellectual life. Millions of people practice Yoga (Hatha Yoga) every morning - in Mumbai apartments, California studios, and Berlin parks - without knowing that Yoga is one piece of a six-part philosophical architecture that ancient Indian thinkers assembled over thousands of years. The other five pieces sit largely untaught, untranslated in spirit if not in letter, absent from school curricula and public discourse alike.

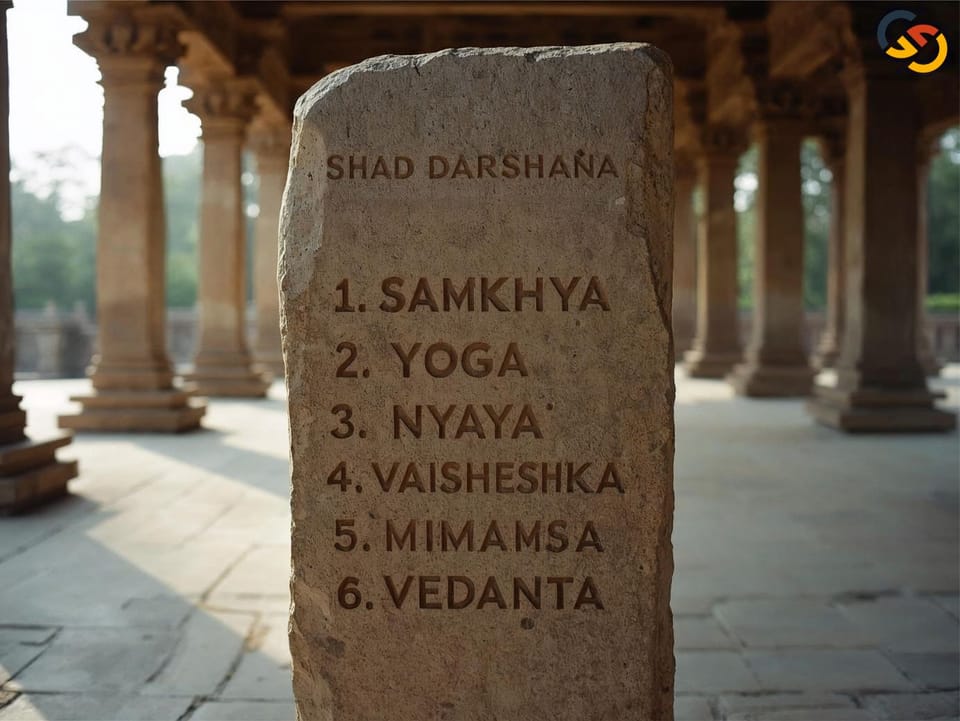

That architecture is called Ṣaḍ Darśana (Shad Darshana): the six visions, the six schools of classical Indian philosophy. And it is, without exaggeration, one of the most ambitious intellectual projects in human history.

This piece is the introduction to a longer series on Sāṃkhya and Yoga - two of those six schools - but to understand either, you need to see the whole map first.

What Does Darśana Actually Mean?

The word Darśana comes from the Sanskrit root dṛś, which means to see, to witness, to experience directly. It is the same root that gives us darshan in the devotional sense - the auspicious sight of a deity or a sage. That etymology matters enormously. In the Indian tradition, philosophy was never merely an intellectual exercise. A Darśana was not a theory to be debated and discarded. It was a way of seeing reality - a complete lens through which a human being could orient their entire existence.

Ṣaḍ means six. Ṣaḍ Darśana, then, is the six visions - a collective term for the six orthodox schools of Indian philosophy that emerged and were codified roughly between 200 BCE and 200 CE, though their roots reach considerably deeper into Vedic antiquity.

What makes these schools "orthodox" (or āstika, in Sanskrit) is their acceptance of the Vedas as a valid source of knowledge. This is not blind deference - several of these schools are essentially atheistic, and all of them engage in rigorous logical inquiry - but they do not outright reject the Vedic testimony. This distinguishes them from the nāstika schools: Buddhism, Jainism, and Cārvāka, which reject Vedic authority in different ways and for different reasons.

Each of the six schools was codified by a founding sage in the form of sūtras - tightly compressed aphoristic threads of thought, dense with meaning, designed for oral transmission and scholarly unpacking across generations. The tradition of commentary on these sūtras - layer upon layer of interpretation by later philosophers - is itself one of the most sustained intellectual endeavours in world history.

The Six Schools and the Questions They Ask

The six schools are paired in an intentional, pedagogically elegant way. Nyāya and Vaiśeṣika form one pair. Sāṃkhya and Yoga form the second. Mīmāṃsā and Vedānta form the third. Each pair addresses a related dimension of reality, and together the three pairs constitute a curriculum close to a complete one for human understanding.

Nyāya - The School of Logic (Founded by Sage Gautama Akṣapāda)

Nyāya means rule, method, or judgment. The school's founding text, the Nyāya Sūtras of Gautama Akṣapāda, is primarily concerned with epistemology - the study of how we know what we know.

The central question Nyāya asks is simple and foundational: how can we trust any knowledge claim at all? Its answer is to identify four valid means of acquiring knowledge, known as pramāṇas: pratyakṣa (direct perception), anumāna (inference), upamāna (comparison and analogy), and śabda (reliable testimony). Nyāya argues that human suffering ultimately stems from mithyājñāna - false knowledge - and that liberation (mokṣa) is achieved through the rigorous removal of such false knowledge.

This is a school that would feel immediately recognizable to a modern analytic philosopher or a scientist. It built the intellectual tools India needed to think carefully. Nyāya was, in a real sense, India's logic.

Vaiśeṣika - The School of Particulars (Founded by Sage Kaṇāda)

Paired with Nyāya, Vaiśeṣika asks the complementary question: once we know how to know, what is the world actually made of?

Sage Kaṇāda - whose name literally means "atom-eater" - proposed a remarkably sophisticated atomic theory of reality. He argued that all physical matter is ultimately composed of indivisible atoms (aṇus), and he developed a system of seven categories (padārthas) to classify all of existence: substance, quality, action, generality, particularity, inherence, and non-existence.

The Vaiśeṣika system is striking in retrospect. Its atomic ontology, its categorization of reality, and its insistence on empirical reasoning place it closer to what we would now call natural philosophy or even early physics than to anything mystical. That Indian thinkers were seriously debating atomic theory in roughly 600 BCE is a fact that has not received the wider attention it deserves.

Together, Nyāya and Vaiśeṣika give you the tools to think (Nyāya) and a model of what exists (Vaiśeṣika). They are the intellectual foundation of the whole system.

Sāṃkhya - The School of Enumeration (Founded by Sage Kapila, the Oldest of the Six)

Sāṃkhya is where the tradition's philosophical depth truly opens up, and it is the system this series will explore most carefully.

The word Sāṃkhya means enumeration or reckoning - a reference to the school's method of systematically mapping all of reality into a set of fundamental principles (tattvas). There are twenty-five of them in the classical Sāṃkhya framework, ranging from the primordial matter-principle Prakṛti down through the faculties of the mind, the sense organs, and the physical elements.

The central question Sāṃkhya asks is searingly personal: why do we suffer, and what is the actual nature of the self that suffers?

Its answer is a radical dualism. Reality consists of exactly two irreducible principles: Puruṣa (pure witnessing consciousness, unchanging, plural, and free from action) and Prakṛti (primordial nature - matter, energy, mind, and everything that can be experienced). The source of suffering, according to Sāṃkhya, is the confusion of these two: the Puruṣa mistakenly identifies with the products of Prakṛti - the body, the ego, the intellect - and thereby becomes entangled in the cycle of birth and death.

Liberation in Sāṃkhya is viveka - discrimination, the clear intellectual recognition of the difference between the witness and the witnessed. When the Puruṣa recognizes that it was never actually bound, the illusion dissolves.

Central to Sāṃkhya's account of Prakṛti are the three guṇas - Sattva (clarity, luminosity), Rajas (activity, passion), and Tamas (inertia, heaviness) - the three fundamental qualities whose interplay gives rise to all phenomenal existence. Understanding these three forces in depth is essential groundwork before diving into either Sāṃkhya or Yoga philosophy in any serious way.

Notably, the classical Sāṃkhya of Kapila is nirīśvara - it does not posit a creator God. Liberation is achieved through knowledge alone, not devotion. This makes it one of the most philosophically rigorous and perhaps unexpected systems to emerge from the Vedic tradition.

Yoga - The School of Discipline (Codified by Mahāṛṣi Patañjali)

If Sāṃkhya provides the map, Yoga provides the vehicle. This is perhaps the most useful single-sentence framing of their relationship.

Yoga Darśana accepts Sāṃkhya's metaphysical framework almost entirely - the dualism of Puruṣa and Prakṛti, the twenty-five tattvas, the guṇas - but adds two crucial elements: a personal God (Īśvara) as an object of contemplation and surrender, and a complete practical methodology for actually achieving the liberation that Sāṃkhya describes in theory.

That methodology is codified in Patañjali's Yoga Sūtras, one of the most compact and consequential texts in the history of human thought. The second sūtra of the text defines the entire enterprise in four words: yogaś citta-vṛtti-nirodhaḥ - Yoga is the cessation of the fluctuations of the mind.

The eight-limbed path (aṣṭāṅga) that Patañjali lays out - ethical restraints, personal observances, posture, breath regulation, withdrawal of the senses, concentration, meditation, and absorption - is not a fitness regime. It is a complete psychological and spiritual technology aimed at untangling the Puruṣa from its mistaken identification with the mind-body complex.

What Yoga actually is - at the level of the Darśana - is something the modern world has largely lost sight of. The Yoga most people encounter today is āsana practice, the third limb of Patañjali's eight, extracted from its philosophical context. That context, rooted in Sāṃkhya Darśana, is what this series will restore.

Pūrva Mīmāṃsā - The School of Ritual Inquiry (Founded by Sage Jaimini)

Pūrva Mīmāṃsā - literally "earlier investigation" - is the most worldly of the six schools. Its focus is the karma-kāṇḍa section of the Vedas: the portions dealing with ritual action, sacrificial duty, and the dharmic obligations of human life.

The question Mīmāṃsā asks is: how should we act in the world in order to fulfill our sacred duties? Sage Jaimini, in his Mīmāṃsā Sūtras, argued that the Vedas are eternal and self-valid, that their injunctions for ritual and right action are not merely cultural conventions but cosmic laws, and that faithful performance of these duties is the proper path of human life.

What is interesting about Mīmāṃsā philosophically is that it pushes God almost entirely out of the picture - not because it denies the sacred, but because it locates the sacred in the eternal Vedic sound (śabda) and in right action itself, rather than in a personal deity. In some readings, Mīmāṃsā is practically atheistic, yet deeply religious in its orientation. It is the school most concerned with Bhārat's lived social and spiritual order.

Uttara Mīmāṃsā / Vedānta - The School of Ultimate Reality (Codified by Bādarāyaṇa/Vyāsa in the Brahma Sūtras)

The paired complement to Mīmāṃsā is Vedānta - literally "the end of the Vedas" (veda + anta) - which draws on the Upaniṣads, the speculative and metaphysical final portions of the Vedic corpus.

Where Mīmāṃsā asks how to act rightly in the world, Vedānta asks the more piercing question: what is the world, and what is the Self that inhabits it? Its answer, worked out in multiple sub-schools, revolves around the relationship between Brahman (the absolute, undivided reality underlying all existence) and Ātman (the individual self).

Vedānta is not one school but a family. The Brahma Sūtras of Bādarāyaṇa are its root text, but the tradition branched dramatically through the interpretations of three great Ācāryas: Ādi Śaṅkarācārya's Advaita (non-dual) Vedānta, which argues that Ātman and Brahman are ultimately identical; Rāmānujācārya's Viśiṣṭādvaita, which holds a qualified non-dualism in which individual souls and the world are real but inseparable from Brahman; and Madhvācārya's Dvaita, which maintains a strict duality between the individual soul and God.

Vedānta is the most transcendent of the six schools and the one that has had the greatest global influence in modern times, largely through the work of Swāmi Vivekānanda.

The Philosophical Spectrum - Where Each School Sits

One of the most illuminating ways to understand Ṣaḍ Darśana is to place the schools on a spectrum - not to rank them, but to see what ground they each occupy.

Imagine a horizontal axis running from the purely material and worldly on the left to the purely transcendent on the right. On the far left, outside the six schools entirely, sits Cārvāka - the ancient Indian materialist school that belongs to the nāstika tradition. Cārvāka held that only direct sense perception is a valid means of knowledge, that consciousness is a product of matter, that there is no afterlife, no karma, and no liberation to seek. Eat, drink, and enjoy - for death comes for everyone. Cārvāka is philosophical materialism at its most uncompromising, and it deserves credit for forcing every other Indian school to sharpen its arguments.

Moving rightward along the spectrum, Pūrva Mīmāṃsā occupies the most worldly position within the six orthodox schools. It is concerned with this life, this body, these duties, these rituals. It does not dismiss transcendence, but its gaze is firmly on the proper conduct of human existence within the world.

Nyāya and Vaiśeṣika sit in the middle-left - analytical, naturalistic, concerned with understanding the structure of reality through logic and empirical categories. They are the schools of critical inquiry.

Sāṃkhya moves closer to the transcendent side. Its dualism - Puruṣa as pure unchanging consciousness, Prakṛti as the whole domain of matter and mind - lifts the gaze from the world to the distinction between the observer and the observed. And yet it remains intellectual, rational, systematic. It does not prescribe prayer or ritual. It asks you to understand.

Yoga bridges the theoretical and the practical. It takes Sāṃkhya's metaphysical framework and asks: how do we actually live this understanding in the body, in the breath, in the day-to-day workings of a human mind? It is the most experiential of the six schools.

And at the far right sits Vedānta - the most transcendent, concerned not with managing the world or even with liberating oneself from it, but with the radical recognition that the individual self and the ground of all existence are not, at the deepest level, two different things.

This spectrum is not a hierarchy. It is a complete map of the territory of human inquiry. You need the tools of Nyāya to think clearly. You need Vaiśeṣika's ontology to understand what exists. You need Sāṃkhya's dualism to understand the nature of your suffering. You need Yoga's methodology to address it. You need Mīmāṃsā's ethics to live well in the world while you work. And you need Vedānta's vision to understand where all of it is ultimately headed.

Questions about the nature of consciousness have occupied philosophers and scientists across centuries - and as this exploration of sentience and awareness shows, they are no less urgent in the age of artificial intelligence. What the Indian philosophical tradition offers is not mysticism but a remarkably precise and differentiated set of frameworks for approaching those questions.

The Hidden Architecture - Why the Schools Come in Pairs

The pairing of the schools reveals something important about the pedagogical design of the tradition as a whole. The Light of the Spirit Monastery's commentary on the Darśanas, drawing from the century-old Sanatana Dharma textbook of Benares Hindu University, notes that the six schools are best understood in relation to each other rather than in opposition - they form one great scheme of philosophic truth.

Nyāya and Vaiśeṣika together answer the question of epistemology and ontology - how we know, and what there is to know. Sāṃkhya and Yoga together answer the question of liberation - what is the problem, and how do we solve it. Mīmāṃsā and Vedānta together answer the question of the sacred - how do we live it, and what does it ultimately mean?

This is a graduated curriculum, not a collection of competing beliefs. The tradition imagined a complete human journey, from the careful empirical thinker who needs first to trust their own reasoning (Nyāya), through the metaphysician uncovering the nature of consciousness (Sāṃkhya), to the practitioner transforming that understanding into liberation (Yoga), to the sage resting in the recognition of ultimate non-separation (Vedānta). Each pair is a rung on the same ladder.

Why Ṣaḍ Darśana Is Not Taught in Indian Schools

This is arguably the most important and most uncomfortable question.

The answer is not simple; it is a story of layered erasure, inadequate reconstruction, and political choices made by outsiders and by Indians themselves.

The most commonly cited starting point is Thomas Babington Macaulay's infamous Minute on Indian Education, written in 1835. Macaulay's position was explicit: he found no value in the entire body of Sanskrit learning, argued that a single shelf of good European literature was worth the whole of India's native literature, and successfully convinced the colonial administration to redirect educational funding entirely toward English-medium instruction. Sanskrit institutions - the maṭhas, the gurukulas, the tolas that had sustained the living transmission of these philosophical traditions for millennia - lost their patronage, their students, and eventually their teachers.

Later, during the era of Mughal atrocities in India, the perpetrators shifted the center of intellectual gravity toward Persian learning and court culture in northern India. Sanskrit scholarship retreated into temple institutions and regional strongholds. The living culture of tarka - the rigorous philosophical debate tradition in which these schools were sharpened against each other across centuries - began to contract.

Then came independence. Here, ironically, is where the most consequential choices were made by Indians themselves. Jawaharlal Nehru's vision for independent India was explicitly modernist, modeled in significant part on the European Enlightenment tradition. Philosophy in Indian universities came to mean Plato, Descartes, Kant, and Hume. The Darśanas were relegated to optional Sanskrit philosophy courses, touched upon in Class 11 optional philosophy textbooks, and largely absent from the consciousness of educated Indians who went through mainstream schooling.

The framing that did the most damage was this: Indian philosophy was categorized as religion, and religion was categorized as something that secular education systems do not teach. But this framing was itself a colonial import. The Darśanas are not a religion in the sense that European Christianity is. They are rigorous philosophical systems with epistemologies, cosmologies, ethical frameworks, and empirical methodologies. Nyāya's formal logic tradition was sophisticated enough that the medieval school of Navya-Nyāya in Bengal was producing logical notation systems that anticipate aspects of modern symbolic logic. None of this is mysticism.

The cost of losing this living tradition is not merely cultural. It is cognitive. India lost the vocabulary to discuss its own deepest questions about consciousness, ethics, and reality within its own educational institutions. It is a peculiar situation - something like Greece forgetting that Aristotle ever existed.

What Bhārat Lost and What Survived

The loss was not total, and it is worth being precise about what was lost and what survived.

What survived: the yoga āsana tradition, though largely stripped of its Sāṃkhya metaphysical backbone. Advaita Vedānta was carried globally by Swāmi Vivekānanda's late-19th-century work and the continued vitality of institutions like the Rāmakrishna Mission. Temple ritual, which preserved fragments of Mīmāṃsā's ritual philosophy in lived practice. A handful of Sanskrit universities - Varanasi, Tirupati, Puri - that maintained scholarly transmission in isolated pockets.

What was lost: the living discourse. The tarka tradition - the culture of rigorous inter-school philosophical debate in which a Vedāntin and a Naiyāyika would spend days publicly disputing the nature of knowledge and liberation, sharpening both traditions in the process - effectively died. The integration of philosophical inquiry into public life, governance, and education - the idea that the pramāṇas of Nyāya were relevant to how you evaluate any knowledge claim in everyday life - disappeared from mainstream culture.

The gurukula system's replacement with the colonial school model severed perhaps the most important thing of all: the paramparā - the lineage of direct transmission from teacher to student across generations. Texts can be preserved in libraries, but a living philosophical tradition requires living teachers who have themselves practiced what they teach.

What Bhārat lost was not information. It was orientation - a civilizational sense of where these questions fit in the life of an educated, thoughtful person. The universe itself stretches across scales we are only beginning to map - from the cosmic forces pulling entire galaxies across intergalactic space to the flicker of awareness in a single human mind. The Darśanas were Bhārat's attempt to map the inner dimension of that universe with the same rigor we now apply to the outer one.

Why It Matters Now

It would be easy to frame Ṣaḍ Darśana as an artifact of antiquity - impressive, historically significant, but ultimately belonging to a different era. That framing would be a mistake.

The hard problem of consciousness - why there is subjective experience at all, why something it is like to be you exists alongside the neural machinery of the brain - remains entirely unsolved in contemporary philosophy and neuroscience. Sāṃkhya's precise distinction between Puruṣa, as pure witnessing awareness, and Prakṛti, as the entirety of the observable, measurable world, is not a primitive ancestor of modern thinking. It is a live and sophisticated contribution to one of the most pressing open questions in science.

Erwin Schrödinger, the physicist, was explicit about his debt to Vedāntic thought in his book What Is Life? - and he was not alone among 20th century physicists who found that quantum mechanics had dissolved the sharp subject-object boundary that Newtonian physics assumed. The Darśanas never assumed that boundary in the first place.

The $120 billion global Yoga industry is built substantially on a practice whose philosophical roots run directly into Sāṃkhya and Patañjali's Yoga Sūtras. The mindfulness movement draws, often unknowingly, from Yoga Darśana's analysis of citta-vṛtti - the fluctuations of the mind. Cognitive behavioral therapy's core insight - that suffering is produced by mistaken patterns of thought rather than by external circumstances - is a version of what Nyāya called mithyājñāna: false knowledge as the root of duḥkha.

These are not coincidences. They are signs that the questions the Darśanas were built to answer have not gone away. They have simply reappeared in different clothing.

What Is Next in This Series

This piece is the foundation for a deeper dive into the two schools that form the philosophical backbone of the tradition many readers will find most practically relevant today: Sāṃkhya and Yoga Darśana.

The next pieces in this series will unpack the complete Sāṃkhya metaphysical framework - the twenty-five tattvas, the nature of Prakṛti and Puruṣa, and why this ancient dualism is worth taking seriously in the 2nd quarter of the 21st century. From there, we will turn to Yoga Darśana in full - not the eight-limbed path as a fitness curriculum, but as a complete system of consciousness transformation whose logic is inseparable from Sāṃkhya's map.

If you want to begin right now, the three guṇas - Sattva, Rajas, and Tamas - are the most accessible entry point into Sāṃkhya's world. Understanding the fundamental qualities that govern all of Prakṛti will give you the conceptual vocabulary on which the rest of this series builds.

And if your interest in Yoga goes deeper than the mat, revisiting what the tradition actually claims Yoga is for is a natural place to start.

FAQs

What does Ṣaḍ Darśana literally mean? Ṣaḍ means six in Sanskrit, and Darśana means vision, perspective, or way of seeing - from the root dṛś, meaning to see or to experience. Ṣaḍ Darśana therefore means "the six visions" or "the six ways of seeing reality." It refers collectively to the six orthodox schools of classical Indian philosophy: Nyāya, Vaiśeṣika, Sāṃkhya, Yoga, Pūrva Mīmāṃsā, and Vedānta.

Is Cārvāka part of Ṣaḍ Darśana? No. Cārvāka belongs to the nāstika (heterodox) tradition because it rejects the authority of the Vedas entirely. The six schools of Ṣaḍ Darśana are all āstika - they accept the Vedas as a valid source of knowledge, even when they develop highly independent metaphysical positions. Cārvāka is useful as a philosophical reference point because it represents the extreme materialist pole, but it sits outside the Ṣaḍ Darśana framework.

How is Sāṃkhya different from Yoga within the Darśana framework? Sāṃkhya and Yoga are paired schools that share the same fundamental metaphysics - the dualism of Puruṣa (consciousness) and Prakṛti (matter/nature). The key difference is that Sāṃkhya is primarily a theoretical and analytical system: it maps the structure of reality and argues that liberation comes through correct intellectual understanding (viveka). Yoga accepts this framework and adds a personal God (Īśvara) and a complete practical methodology - the eight-limbed path of Patañjali - for actually achieving the liberation that Sāṃkhya describes.

Are the six schools of Ṣaḍ Darśana still practiced today? Yoga is the most actively practiced by a vast margin, though often in forms separated from its philosophical context. Advaita Vedānta remains a living tradition through institutions such as the Rāmakrishna Mission and numerous Vedānta societies worldwide. Mīmāṃsā survives in the ritual practices of trained Vedic priests. Nyāya and Vaiśeṣika are studied primarily in academic Sanskrit philosophy departments and traditional pāṭhaśālās. As a unified and living intellectual culture - where all six schools are taught and debated together - Ṣaḍ Darśana has not been practiced in its full form for several centuries.

Is Ṣaḍ Darśana the same as Hinduism? Not exactly, though they are deeply connected. Hinduism, as a lived religious tradition, encompasses worship, mythology, ritual, ethics, and social practice that extend far beyond the six philosophical schools. Ṣaḍ Darśana specifically refers to the philosophical and intellectual dimension of the tradition - the systematic attempt to reason about reality, consciousness, liberation, and knowledge. All six schools accept the Vedas as authoritative, linking them to the Hindu tradition, but several of them (especially Sāṃkhya and early Mīmāṃsā) are effectively atheistic in their metaphysics.

Which is the oldest of the six Darśanas? Sāṃkhya is generally considered the oldest of the six schools, with its roots attributed to Sage Kapila and its ideas traceable in the earlier Upaniṣads and in the Mahābhārata. Its formalized text, the Sāṃkhya Kārikā of Īśvarakṛṣṇa, dates to roughly the 4th-5th century CE, but the underlying ideas are considerably older. Many scholars note that Sāṃkhya's philosophical framework appears to predate even its attribution to Kapila, suggesting an even more ancient lineage.

Why did Indian schools stop teaching classical Indian philosophy? The story has several layers. Macaulay's 1835 Minute on Indian Education redirected colonial educational funding entirely toward English-medium instruction, defunding Sanskrit institutions. The Mughal period had already contracted Sanskrit scholarly patronage in some regions. After independence, the Nehruvian secular-modernist framework categorized the Darśanas as "religious" rather than philosophical, keeping them out of mainstream secular curricula. Western philosophy - Plato, Descartes, Kant - became the default in Indian universities. Today, the Darśanas appear only in optional philosophy courses and as brief mentions in history textbooks, absent from the core curriculum that the vast majority of Indian students encounter.